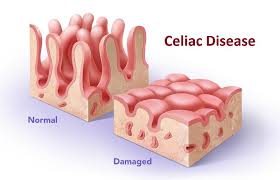

Those familiar with celiac disease (CeD) know that symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and lactose intolerance are commonly associated with CeD. Unfortunately, for a significant portion of children who have CeD, these symptoms often do not present themselves as one would expect. Some with CeD are asymptomatic, while others have symptoms that are often confused with other medical issues, such as IBS. In fact, research suggests that as low as 10% of those with CeD are actually properly diagnosed. This has sparked much debate in the scientific community over the questions of how, when, and which children should be tested for CeD. Some doctors, such as Joseph Murray, MD, a member of the Medical Advisory Board for Celiac Disease Foundation, who will speak at the 2015 CDF National Conference & Gluten-Free EXPO, advocate the importance of research given CeD’s increasing prevalence. He states in an article from the New York Times that “Celiac disease is now five times more common than it was 50 years ago, and that’s not just the result of better diagnoses.” Considering the rising number of cases of CeD, and its extremely detrimental effects on childhood development, leading to malabsorption and failure to thrive, it is becoming more necessary to find a means to properly diagnose these young children.

Those familiar with celiac disease (CeD) know that symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and lactose intolerance are commonly associated with CeD. Unfortunately, for a significant portion of children who have CeD, these symptoms often do not present themselves as one would expect. Some with CeD are asymptomatic, while others have symptoms that are often confused with other medical issues, such as IBS. In fact, research suggests that as low as 10% of those with CeD are actually properly diagnosed. This has sparked much debate in the scientific community over the questions of how, when, and which children should be tested for CeD. Some doctors, such as Joseph Murray, MD, a member of the Medical Advisory Board for Celiac Disease Foundation, who will speak at the 2015 CDF National Conference & Gluten-Free EXPO, advocate the importance of research given CeD’s increasing prevalence. He states in an article from the New York Times that “Celiac disease is now five times more common than it was 50 years ago, and that’s not just the result of better diagnoses.” Considering the rising number of cases of CeD, and its extremely detrimental effects on childhood development, leading to malabsorption and failure to thrive, it is becoming more necessary to find a means to properly diagnose these young children.

Laura Pullen presents scientific results and opinions of multiple researchers in her article “Celiac Disease: Which Children Should Be Tested?” She notes that some researchers suggest a simplistic answer: every child should be given an antibody test panel to determine if they are likely to have the disease. What these panels include varies within the medical community, but most test common indicators of CeD, such as antitransglutaminase (anti-tTG) and total immunoglobulin A (IgA). Other doctors suggest a more selective, cost- and time-effective approach, administering tests specifically to those who show classic symptoms and confirming with an endoscopy and biopsy, as the possibility of false positives and negatives can trouble parents with the uncertainty of the results.

Another factor that complicates diagnosis for children is that symptom presentation may not always be correlated with the presence of the disease. Edwin Liu, MD, co-author of “Clinical Features of Celiac Disease: A Prospective Birth Cohort,” works to ensure the health of celiac patients and will join Marilyn Geller, CEO of Celiac Disease Foundation, to present to Dr. Susan T. Manye, Director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, on April 15th in Washington, D.C. Laura Pullen summarizes the result of this study in her article and states, “Researchers report that anti-tTGA levels correlate with severity of mucosal lesion in symptomatic and asymptomatic children, and some asymptomatic children had quite elevated levels of anti-tTGA.” This means that within the study, even children with CeD who did not present classic symptoms showed elevated levels of the anti-tTGA marker. Children enrolled had only discovered that they had CeD as a result of the study because they lacked symptoms or were presumed to have other medical conditions. Using this information, scientists have created a proposal for a two-tiered screening system where newborns are screened for genetic precursors, and if positive, then screened by an antibody panel.

Another factor that complicates diagnosis for children is that symptom presentation may not always be correlated with the presence of the disease. Edwin Liu, MD, co-author of “Clinical Features of Celiac Disease: A Prospective Birth Cohort,” works to ensure the health of celiac patients and will join Marilyn Geller, CEO of Celiac Disease Foundation, to present to Dr. Susan T. Manye, Director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, on April 15th in Washington, D.C. Laura Pullen summarizes the result of this study in her article and states, “Researchers report that anti-tTGA levels correlate with severity of mucosal lesion in symptomatic and asymptomatic children, and some asymptomatic children had quite elevated levels of anti-tTGA.” This means that within the study, even children with CeD who did not present classic symptoms showed elevated levels of the anti-tTGA marker. Children enrolled had only discovered that they had CeD as a result of the study because they lacked symptoms or were presumed to have other medical conditions. Using this information, scientists have created a proposal for a two-tiered screening system where newborns are screened for genetic precursors, and if positive, then screened by an antibody panel.

With all of these proposals from educated scientists kept in mind, a few things are clear: if a child has symptoms of CeD professionals suggest that they be tested first with an antibody panel, and if positive, followed with an endoscopy and biopsy. The conversation is still open to debate in the medical community regarding the rest of the population. It is clear that many are left undiagnosed who do not present the typical symptoms of CeD and the crucial next step to improve diagnosis of these individuals is emphasized.

For more information on common symptoms to help determine whether or not your child should be tested, visit here.